The Z Beans Coffee Story - A Narrative

The Z Beans Coffee Story - A Narrative

Baseball was all I knew. For 20 years, I dreamt of playing under the lights at Turner Field. Dad and I would throw the ball in the front yard whenever he got home from work. At 7:05, I’d sprint back in the house to watch the Braves play. This was my childhood.

As a teenager, the dream grew. Everything I did, whether it was in school, hanging out with my friends, or on the field, was intentional. I’d wake up before school, at 5, to workout; I needed the afternoons to work on my craft. The afternoon would come, and I’d long toss, hit off the tee, or work on specific drills. The harder I worked - the more it meant to me. By the time I was 14, baseball was no longer a game; it was life.

Six years go by, and the same problem haunts me over and over again. How do I seperate thinking in the classroom from thinking on the field? I can’t do it. I’m emotionally invested into the game - it’s the only thing I’ve ever known. Every decision I’ve ever made has been with baseball in mind. I never drank alcohol because I didn’t want to hinder my performance in any way - I never went out because I needed to wake up early the next morning - I never forsaken life because the law of reciprocity would have doomed my career.

I’m superstitious - I’m an overthinker. On November 12, 2015, my baseball career ended. I was cut from the Mercer University baseball team. Baseball is a game of failure. As a perfectionist, as a very passionate individual, I could never let go of the errors - of the strikeouts - of the missed opportunities. Quite frankly, I wasn’t good enough.

It hurt. I sat on the phone with my father, and I cried. He said, “Son, we will always be proud of you.” I sat on the grass that night, behind the Stetson School of Business, staring off into the distance. Little did I know, the Religious Life Center building, which stood in my line of sight, would bring me new life.

Waking up the next morning, for the first time, I no longer had a purpose. I no longer had a project that I could work on. All I was left with was my two majors, economics and Spanish.

One day, during the spring semester of 2016, I was walking out of my economics of sports class, and I saw a poster on the wall of the Stetson School of Business: ‘Economics trip to Ecuador - as part of Mercer On Mission.’ I had never heard of Mercer On Mission up to this point, but it peaked my interest. I’d not only go with an economics group, but I’d be able to improve my Spanish as well. It seemed like a match made in heaven.

I did some background research on the program, and I found that I’d be able to take an upper-level Spanish class as well as an upper-level economics class. I wouldn’t have to pay for my plane ticket, either. I only had to pay for the cost of tuition. When I presented the idea to my mother and father, they liked it. Naturally, my mom was worried about me leaving the country for the first time, but I steered her away from those fears. My parents both agreed - I should go.

I attended the info sessions and submitted my application. I was accepted into the program, pending a positive report from Dr. Mengolini, a Spanish professor at Mercer. She needed to access my Spanish speaking abilities; I needed to be well versed to conduct interviews in Ecuador. This was a major obstacle for me to overcome because I knew my Spanish wasn’t good enough. But, I also knew that if I prepared for the talk with Dr. Mengolini, I’d leave a positive first impression. So, I spent a few days brainstorming possible questions she’d ask. I came up with 15 different scenarios. I memorized 5 sentence answers to each one.

The day comes - it is time to interview. I stand in front of my mirror in my dorm room of Shorter Hall and rehearse my answers. I’m ready. I head over to Knight Hall and find Dr. Mengolini’s office. We jump into the interview, and sure enough, 4 of the major questions she asks me, I’ve already prepared for. We have a terrific conversation, and she approves my Spanish. I’m all set - I’m heading to Ecuador.

Three months later, the times has come to leave the country. While I knew it would be an interesting experience, I did not know what to expect. It was not only my first time out of the country but my first time ever flying on a plane. Mercer has worked in Ecuador over the past 6 years. Initially, the project was focused on helping the small scale artisanal gold mining sector in the El Oro region, particularly in the cities of Zaruma and Portovelo. However, problems with gold mining exacerbated. The initial goal of finding safe ways to discard of mercury waste was no longer enough. The local government of Zaruma reached out to Mercer, asking them to gauge whether coffee is a viable economic alternative to gold mining.

This was our task. Specifically, the business students would collect data and analyze the significance, and the Spanish students would conduct the interviews. I would have the opportunity to not only conduct the interviews but analyze the significance of the findings as well. I looked forward to learning more about international economics and improving my Spanish. However, little did I know, the trip would turn out to be so much more.

We flew into Quito, the capital, then caught a connecting flight that took us into Santa Rosa, also known as Machala. From there, we took taxis up to Zaruma, which was almost an hour and a half away. Upon arrival, we break up into our groups. There is a chemistry, engineering, Spanish, and economics group. We set the agenda for the next three weeks; we plan to begin the interviews in three days.

When the day came to interview the farmers, we weren’t sure what to expect. Dr. Saravia, our economics professor, tells us that a bus will shuttle us around. At 9am, a blue bus with bench style seats parks in front of our hotel. We all climb aboard and prepare for the trek. After travelling up the side of the Andes Mountains for an hour, we finally reached our first stop. Arturo, a government employee in Zaruma, Ecuador, who was tasked with serving as our tour guide, asked for two groups of two. I made up one of the groups. Arturo told us that there would be farmers throughout the area and that we would stop at the houses to conduct the interviews. However, after walking over a mile, the initial house had yet to be seen. We were getting tired of walking, yet Arturo, a 65-year-old man, showed no signs of fatigue. Eventually, we came to the first house and conducted an interview, but the most meaningful message was already taught.

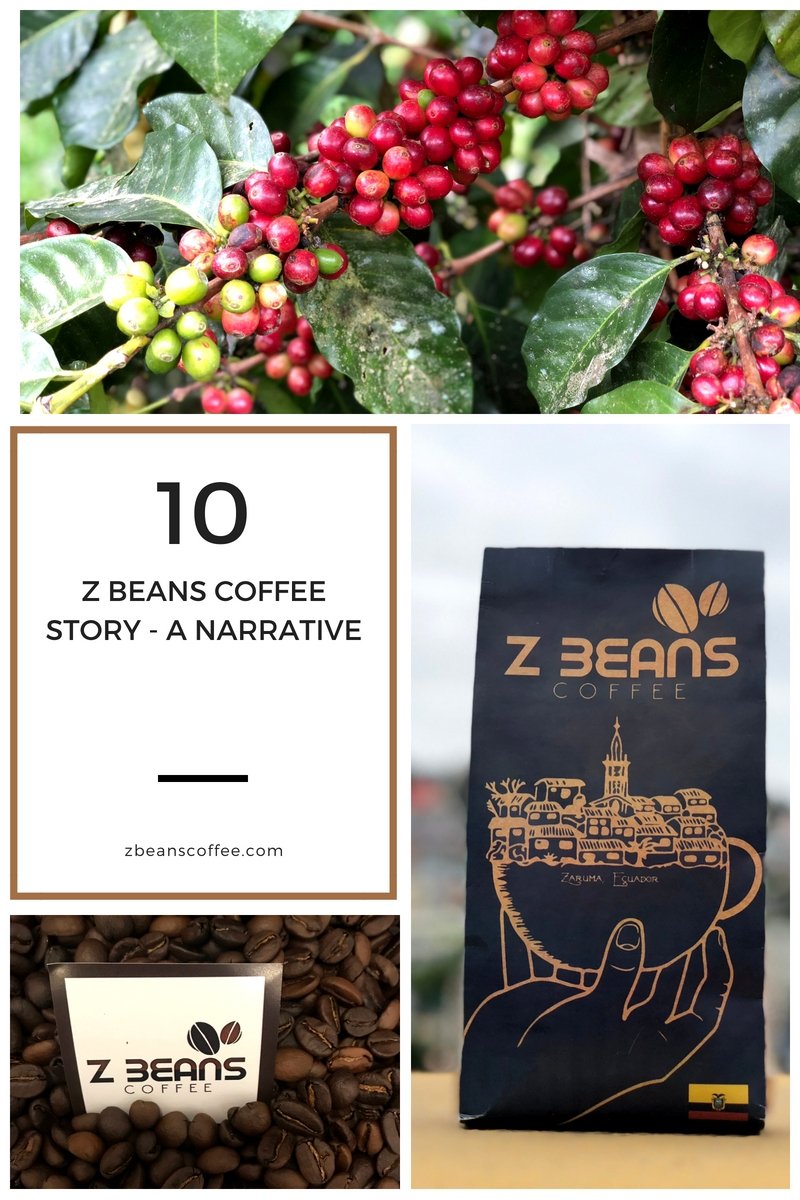

We continued to conduct interviews over the next couple of weeks. We found that, on average, farmers in the El Oro region of Ecuador only had a primary school education. Furthermore, we found that the reason for a lack of coffee production in the region was due to a lack of demand. When we went to the different farms, we were given different coffees to try. Up to this point in my life, I had never tried coffee. My parents never drank it, so it was never in my house growing up. I thought the coffee was good, but I had no comparison. Everyone else thought it was good as well.

After two and a half weeks, we sat down and analyzed our findings. We tallied up the entire amount of coffee we seen, and it was a mere 2,000 pounds. Rationally, we concluded that there simply wasn’t enough coffee in the region to create any sort of business. So, for the remaining time in Ecuador, I decided to fully immerse myself into the culture. I started talking regularly with Arturo and the other government officials. Before we left, Arturo even invited me to his house for dinner. This immersion helped me improve my Spanish, but most importantly, this immersion created a friendship. Through our talks, the message that I was taught during that long, hot trek up the Andes became increasingly clear. I realized just how hard the people of Ecuador work. While I pride myself on hard work, I fail to compare to the men and women of Ecuador. From that day on, I made it a mission. I’ve always been rewarded for my work, and it is time that the people of Ecuador are as well.

After three weeks, it was time for the Mercer on Mission crew to leave. I said my goodbyes to Arturo and his family, but I assured him our friendship was far from over. We exchanged phone numbers, and Arturo asked me to call him once every week, so I could continue to improve my Spanish. When we returned to the United States, I held to my end of the promise. We spoke once a week at first, but as the conversations became more beneficial, we started speaking 4-5 times a week. One day, as we were struggling to find something to talk about, Arturo asks, “What do you think about starting up a coffee business, importing Ecuadorian coffee?” I said to him, “Arturo, I love that idea. But, there isn’t enough coffee in the region. We were just down there. We only found 2,000 pounds.” The next day, Arturo sends me a list of 43 farmers, willing and able to supply coffee.

I was intrigued, but quite frankly, I had no idea where to begin. So, I started researching, trying to learn as much as I can about coffee importing. I figured - if I can’t import the coffee into The States or get it out of Ecuador, then there is no need for me to even waste my time with this project. However, the more I read, the more I realized that this truly isn’t a difficult task. The key factor would be whether or not I could formulate the appropriate connections to get it out of Ecuador. Since the El Oro region of Ecuador had yet to import on a global scale, the proper infrastructure was not in place. There weren’t cooperatives that helped the farmers. So, I told Arturo that we would need to find a freight forwarder, a leader of the AGROCALIDAD (the Ecuadorian version of the FDA), and a processing facility that I could register with the FDA. My plan was to connect the freight forwarder with one in The States, have the AGROCALIDAD leader inspect the coffee and approve it for export, and use the processing facility to peel and sort the coffees.

After 8 months of hard work, Arturo and I completed the supply chain. Arturo made the appropriate connections for us internationally, and we were set to go. We imported 65 pounds of coffee, and I gave it to different connoisseurs that I knew. The coffee was very well received. After the 65 pound batch, I wanted to import 300 pounds. The 300 pounds would be our first ‘cargo size’ shipment, which requires greater legal measures. In early July, Arturo sends out the 300 pounds from Guayaquil, Ecuador. I expect to receive the shipment on July 10, 2017, which would give me plenty of time to roast the coffee before I head to Ecuador on July 18 to purchase a much larger sum.

July 10 rolls around, and the coffee is nowhere to be seen. I get a call from an official in the Miami International airport, telling me the coffee had arrived. He tells me that the cargo had my name as the ‘certified received.’ Thus, no power of attorney document will help me because I am the only one who may pick it up. The official tells me not to worry, though. The coffee will be in Savannah, GA, by July 12. July 12 comes - still no coffee. I call the freight forwarder that I’m working with out of Miami, and he tells me that the coffee has been held up because the airport is waiting for the most economical time to ship. Needless to say, the coffee didn’t arrive until July 25.

On July 18, as planned, I returned to Ecuador. Arturo and I visited multiple farms and collected 4,000 pounds of coffee. Learning from the previous mistake, I made sure to fill out the airway bill correctly. Our freight forwarder received the 4,000 pounds on our behalf on August 7. I received the 4,000 pounds 10 days later on August 17, 2017, signaling the birth of Z Beans Coffee.

I spoke with Dean Gilbert, the dean of the business school; Dr. McClung, the associate dean of the business school; and Mrs. Howard, a marketing professor at Mercer, about the project. They graciously gave me space in the Mercer Innovation Center to not only store my 4,000 pounds but to roast, grind, and package it. The Mercer Innovation Center is a new building on campus, beginning during fall of 2016. It use to be the religious life center - the building that stood in my line of sight as I contemplated life after baseball.

Currently, I work on Z Beans like I once worked on baseball - with its best interest always in mind. I roast the coffee in the Mercer Innovation Center on Mercer’s Undergraduate Campus. I started by roasting 11oz at a time in a popcorn popper, but I have since moved up to a 5-pound roaster. I am working to find sales channels for the coffee. At the core of Z Beans mission lies the ultimate goal: to help as many farmers in the El Oro region of Ecuador as we can. I understand that the way for me to do this is to import as much coffee as possible. I am exploring wholesale opportunities, but I am also focusing on building the Z Beans brand.

No matter what happens with Z Beans in the future, I will always be grateful for the connections I have made and the countless international business tips I have learned. I have always wanted to pair my Spanish, economics, and marketing degrees, and I believe I have found the perfect way – development work in Latin America. I have lofty goals for the future, but I am most excited for the opportunities Z Beans will bring to the people of Ecuador.

Mercer On Mission led me to my true calling. It restored the sense of purpose in my life that I lost after baseball was taken away. The friendship that I made with Arturo Penarretta Romero will be one that I will always cherish. I will never forsake him, as I trust that he will never forsake me. He has unconditionally confided in a young 22 year old, and for that, I’m grateful. While it may have been destiny for Arturo and me to meet, Mercer On Mission offered a platform for fate to run its course. A platform to change the world.

Thank you for the continued support!

Your friend,

Shane Buerster

Z Beans Coffee Founder & CEO

2 comments

I am am architect.

I love coffee.

I love helping people.

Your story is amazing.

Your product is amazing.

Hello, Shane! My daughter and I came up to Macon last weekend to check the campus out “one more time” before May 1 rolls around, and we ended up at Z Beans. We didn’t know anything about the “why” of your mission, but after reading your story, it all makes sense. I finally had time this morning to brew a cup of Herman’s coffee, and you were absolutely correct – it is really smooth and full of flavor. God bless you, your farmers, and your mission. I’m so glad you found the Mercer on Missions door after baseball!